Introduction: The Groton-Dunstable Regional School District (GDRSD) is a pre-kindergarten through twelfth-grade regional district located 45-miles, northwest of Boston, Massachusetts. For the 2019-2020 school year, GDRSD enrolled 2,353 students and employed 181.8 teachers, accounting for a 13.2-to-1 student-to-teacher ratio (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). The GDRSD school committee approved a district vision committed to the belief that all students can achieve at high academic levels when instructed in a universally designed teaching and learning model. Furthermore, all personnel, including administration, instructional, and support staff, should strive to eliminate inequities for all students (About us – GDRSD district, 2020).

The responsibility for carrying out this vision was assigned to the district administration, and then, to GDRSD’s teachers. The expectation for this transformational leadership was to embrace a growth mindset, push to eliminate inequities for all students, and foster innovative classroom environments. The GDRSD vision dovetails with existing district initiatives, such as the Strategic Technology Plan and Needs Assessment Report, to implement a universally designed, tiered instructional model to empower students to be self-directed, creative problem solvers. Additionally, as a part of a collaborative visioning process within the community, considerable energy has been expended in support of teachers, including refining the evaluation system, creation, and implementation of professional learning communities centered around data-informed decision making, expectations of inclusive practices, and adoption of state-standards, each in an effort to support learner variability and eliminate inequity when exposed. It remains a priority to support teachers, in all facets of their positions, because exemplary instruction is the most critical method to positively impact student achievement and allow for equitable outcomes (Elmore, 2004; Leithwood et al., 2004).

Continuing in this vein, synthesizing over 1,600 meta-analyses, involving over 300,000,000 students, Hattie’s (2018) visible learning research focused on public schooling and effect sizes that influence student achievement. With 252 factors listed and an average effect size of 0.4, collective teacher efficacy (1.57) is listed as having the greatest effect on student outcomes (Hattie, 2018). After technological infrastructure barriers have been overcome—ubiquitous access to the Internet and Internet-enabled devices—a teacher’s education and beliefs, or efficacy, on educational technology integration have the greatest influence and are central to the implementation of technology within the classroom (Drent & Meelissen, 2008; Gilmore & Ross, 2020; Hattie, 2018; Prestridge, 2012; Sang et al., 2011).

By most measures, GDRSD is a high-performing school district. Students arrive each day ready to learn. A dedicated staff of licensed-instructional leaders, as well as non-instructional support personnel, allows students to meet or exceed nearly all accountability measures from annual assessments on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). On overall progress toward student growth targets, which include English language arts and mathematics achievement indicators, GDRSD has a cumulative criterion-referenced target percentage of 84% (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). This target percentage signifies how GDRSD performs when compared to other districts across the state. In GDRSD’s situation, the district is meeting and/or exceeding its student growth targets better than 84% of districts within Massachusetts. However, accountability trends are on a decline for the high needs subgroup, which includes economically disadvantaged students.

With a recent change in definition and move away from low-income status, the Massachusetts Department of Secondary and Elementary Education (DESE) defines economically disadvantaged as a student’s participation in one (or more) of the following state-administered programs: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Transitional Assistance for Families with Dependent Children (TAFDC); the Department of Children and Families (DCF) foster care program; and MassHealth (Medicaid) (Redefining low income, n.d.). As a reference point, for a family of three to remain eligible within the TAFDC program, the monthly income allowance from the parent(s) of a child under the age of 18 is $3,620.00 (Department of transitional assistance, 2020). With a metric of poverty changing its definition to economically disadvantaged, DESE’s intention was to lessen paperwork and administrative burden. Instead, the changes have confused exactly who is contending with financial hardship. However, as Edward Moscovitch, a researcher who developed the Commonwealth funding formula that included a broader low-income definition shared, “how can the state determine what’s working to improve low-income students’ performance if it can’t locate and track those students?” (Larkin, 2019, para. 8).

Within the last decade, GDRSD has experienced substantial cuts to staffing and programming. Budget shortfalls within the local funding process and failure of operational overrides at local town meetings have forced larger class sizes and loss of programs, which are likely catalysts for lowering academic achievement. Only over the past several fiscal years was staffing restored to adequate levels to support the vision for academic programming and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) infused instruction. With financial resources limited, recommendations by the district administration, included in the Needs Assessment Report, identified priorities in which the district must take action. The cost-saving analysis performed by an outside consultant, captured in the Needs Assessment report, supported programmatic changes to staffing levels, curriculum and assessment materials, school committee communication methods, and management and operations cuts in order to provide funding to further grow academic achievement for all students. However, there are still subgroups of students, specifically economically disadvantaged students, failing to close the academic achievement gap between all students, which will be reviewed during this exploration.

Statement of Problem

Fourth-grade students labeled economically disadvantaged are performing significantly lower on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) in English Language Arts than fourth-grade students that do not have this label. Overall, economically disadvantaged students have a range of adverse consequences to overcome, and with inadequate improvement for this group of children in recent history (Ander et al., 2016). Furthermore, just some of the consequences facing economically disadvantaged students include lower academic outcomes on testing (Freedberg, 2019), concerns with self-regulation (Howse et al., 2003), increases to the reading achievement gap during school breaks (Allington et al., 2010; Schacter & Jo, 2005), gaps in preparedness for kindergarten, with impacts felt through an entire academic career (Garcia & Weiss, 2017) and many more.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to examine (and elicit further discussions) how district and instructional staff can better deliver pedagogical and technological principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in an effort to align best practices that will close the academic achievement gaps in MCAS testing among economically disadvantaged students in the fourth grade. Further research is needed to examine systemic and instructional root causes for a widening of the achievement gap for economically disadvantaged students. The district’s commitment to a standards-focused curriculum within all subjects of the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks, in particular, English language arts, and the incorporation of the UDL framework is important to note, but only with a modicum of success for this sub-group of students.

Research Question

How does universally designed instruction at GDRSD impact academic outcomes of economically disadvantaged fourth-grade students in the subject area of English language arts?

Significance

Beginning in 2014, GDRSD has contended with ways to sustain and provide a context of UDL infused instruction in all subject areas, but in particular English language arts and literacy instruction. Instructional approaches along with lags in curriculum development and lack of a complete adoption of standards are likely at play for recent drops in academic achievement. Since the implementation of the Common Core State Standards, adopted as the Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for English Language Arts and Literacy in 2010 and updated in 2017, there have been declines across the nation in literacy (Barnum, 2019) and these declines have also taken place at GDRSD. As included in the district visioning process, eliminating inequities for all students, especially economically disadvantaged students, is a priority, with a universally designed, tiered instructional model at its core. UDL instructional approaches alongside essential English language arts standards should be symbiosis and with positive impacts on learning outcomes.

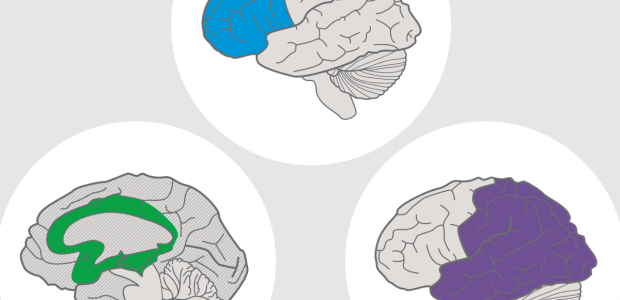

UDL principles have a foundation entrenched in modern neuroscience and can be best defined as a framework that eliminates barriers and a “framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all” (Cast, 2018, para. 2). The approach to district-level UDL implementation requires consideration for not only student variability but also technology-related obstacles and consideration for the necessary time and learning styles amongst staff. There is consensus that educational organizations need to build capacity for managing high-level changes that UDL adoption, and secondarily technology integration, demand (Hall et al., 2015; Meyer & Stensaker, 2006). Through a universally designed lens, GDRSD seeks to support, as Meyer et al. (2014) have shared, a curriculum and instructional approach that develops expertise as a learner and maintains innovative learning environments in support of continuous development of self. Further, as the instructional staff who have received training on the UDL framework and have subsequently retired (or left) from GDRSD, the teacher preparation within higher education does not mandate or incorporate UDL best practices infused with technology (Moore et al., 2018; Nepo, 2017). GDRSD pre-service and current teachers often lack an effective approach or “hook” to integrating technology into their classrooms, which aligns well with the UDL framework (Russell et al., 2003).

Tangential to the statewide assessment data, GDRSD captures other internal measures in the English language arts, as a means of adjusting UDL infused instruction and developing academic interventions. Teachers must raise their grading practices and increase expectations for all students as an important measure toward increasing academic achievement on MCAS. Research by Gershenson (2020) shares that awarding higher report-card grades to students who score poorly on statewide assessments indicates a weak curriculum and low academic standards. Gershenson (2020) continues that all student subgroups have significantly improved learning outcomes when teachers have higher grading standards, placing a great deal of responsibility on the teacher. “We must learn how to make high expectations and high grading standards a part of the teaching culture through hands-on teaching, optimized incentives, and stronger professional development” (Gershenson, 2020, p. 35).

Status of UDL Implementation

GDRSD seeks to increase academic achievement as an expected outcome for all students, with an emphasis on the high needs population, including economically disadvantaged students and the variability in learning inherent in all students. Through the adoption of UDL and a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS), district leadership pursued foundational and research-supported systems that are rooted in best practices and national research. Rather than remain stagnant, district leadership has been proactive in implementing both academic support systems and is likely years ahead of some comparatively located and sized districts. “Good leaders know when it is time to change and when it is not—when inertia should be left alone and when it should be challenged” (Marion & Gonzalez, 2014, p. 361).

Although reliant upon Universal Design (UD), which originated in the 1970s, UDL was only expanded upon in the realm of effective pedagogy and learning in the early 2000s (Meyer & Rose, 2000). With UDL only scratching the surface and a relatively new framework in public education, GDRSD has made significant strides offering professional development opportunities throughout the year focused on instructional and technology integration strategies on the principle that “all students are capable of success” (Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education, n.d., p. 2). With foundational development of MTSS infused with UDL, GDRSD is no longer reactive to student achievement declines and is instead supporting “a comprehensive continuum of evidence-based, systemic practices to support a rapid response to students’ needs, with regular observation to facilitate data-based instructional decision making” (ESSA, 2015, p. 2093).

The district professional development committee has connected scarce time and resources to more meaningful implementation of UDL, including in-service sessions, graduate-level courses, as well as continued direction and leadership from district personnel, including principals, technology support staff, curriculum coordinators and coaches. Also, there has been considerable time and resources spent on informal discussions surrounding effective teaching practice and the necessary reflection required to implement a change in practice. Papa (2010) notes the importance of providing teachers with time to reflect on their own practices when implementing a change initiative by providing sufficient “opportunities to practice and observe, and opportunities to be coached and coach others” (p. 15).

Research by Meyen (2015) raises the bar that both technological and educational advancements are meshing in meeting the needs of diverse learners. Further, incorporating digital tools in the classroom can anticipate learner variability and reduce barriers using UDL as an effective delivery instructional method (Nepo, 2017). GDRSD instructional staff are working towards embracing technology as a delivery method for instruction in conjunction with the UDL framework, however, achievement gaps persist.

Economically Disadvantaged Students and Assessment Data

Economically disadvantaged students represent 8.9% of the GDRSD student population and are being outperformed by all students, at all grade levels, using the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) metric (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). When examining student achievement, there are other assessments the district considers. However, MCAS is given the most significant in the student academic profiles. In grade four, in the group of all students, non-economically disadvantaged, 77% are meeting or exceeding the ELA MCAS assessment for 2019. Whereas 38% of economically disadvantaged students are meeting or exceeding the ELA MCAS assessment. Important to consider is similar downward trends shown in Mathematics MCAS and slight declines among the Science MCAS achievement results. With DESE creating a new MCAS assessment, including formula changes to accountability measures and updates to subgroup definitions, it is difficult to find overarching trends in MCAS data prior to 2018, especially when factoring in different grade-level cohorts. However, prior MCAS assessment data in 2018 can be compared to the current 2019 data and there is a noted downward trend. For grade four, all students, non-economically disadvantaged in 2018, 69% met or exceeded the ELA MCAS assessment, and 55% of economically disadvantaged students met or exceeded the ELA MCAS assessment. In comparison from 2018 to 2019, the non-economically disadvantaged students’ achievement increased by 8%, while the economically disadvantaged students decreased by 17% on the ELA MCAS assessment.

UDL, Digital Tools can Support Meeting the Needs of All Students

As Director of the Department of Technology & Digital Learning, this author searches for better alignment between the integration of technology and universally designed learning principles in support of increasing academic achievement for economically disadvantaged students. As instructional practices shift towards UDL, the Department seeks involvement in the creation of standards-based lessons, assessments, and supporting staff in best teaching practices. The Department and Director must increase knowledge on the integration of UDL and technology-enhanced learning, which can promote practical approaches in delivering instruction to meet the needs of all students in all educational environments (Hall et al., 2015). As Moore et al. (2018) have shared in their research, UDL principles often fail to catch on because of their complexity, the required knowledge by teachers and not having a critical issue in which to alter the course. With recent MCAS data highlighting an unfavorable achievement gap widening for economically disadvantaged students, the critical issue is now front and center.

Many students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds underperform their peers in reading and literacy assessments, which has been linked to intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy (Guthrie et al., 2009; Ng, 2018). Schmoker (2020) concisely shares that literacy “is the single most important goal of schooling and the key to academic and career success.” When a teacher supports motivation and student’s voice—sharing of ideas and perspectives—through purposeful reading engagement, for example, allowing reading materials to be brought in from home, a stronger student-teacher relationship can be formed and school outcomes improved for economically disadvantaged students (Ng, 2018). Further, Ng (2018) interprets engaging economically disadvantaged students by carefully listening to their views and establishing “contexts that give rise to the life histories, personal experiences, and beliefs which underpin their voices” (p. 703). Continuing to promote reading engagement and student choice is significant as it contributes to the teacher’s knowledge to continue to develop more engaging reading practices (Rudduck & Fielding, 2006).

Since the adoption of the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks and subsequent updates, the major focus of English language arts instruction is teaching students to write well in a variety of genres and formats, both digital and analog, while using technology for collaboration. Application of writing across the curriculum, for example, in the subject of science, is worthwhile, with outcomes supporting economically disadvantaged students to “acquire academic language and conceptual understanding” (Huerta et al., 2014, p. 1850). Further, economically disadvantaged students who participated in writing interventions obtained higher scores on statewide standardized writing tests than those students who did not participate in the academic interventions during this same time (Amaral et al., 2002).

At GDRSD, all students are provided a classroom-based Google Chromebook in a 1:1 computing environment, allowing access to creative and innovative learning attempts throughout the school day. Research has found positive conclusions surrounding the benefits of ubiquitous 1:1 technology access in the classroom, regularly sharing positive effects in English language arts achievement data (Clariana, 2009; Zheng et al., 2016). According to Calkins et al. (2015), “writing is a subject in which the quality of students’ work can improve in only a matter of weeks in ways that are visible to both (the teacher) and students” (p. 3). Similarly, in another study, research by Lee et al. (2005) shared that elementary-aged, economically disadvantaged students participating in science and literacy interventions exhibited substantial gains in writing achievement measures captured during the course of a year. With visible growth shown in such a relatively short period of time, it is important to identify methods that take advantage of improvements measured in weeks, not years, or longer. A standards-aligned focus requires students to show their understanding and mastery of the Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for English Language Arts and Literacy in Writing and the ideal can be bolstered across all subjects with adjustments to instructional practice, which include research-supported academic interventions and stronger teacher-student relationships, which are shown to increase academic achievement.

Conclusion

Rooted in adopting district-wide UDL implementation in support of closing achievement gaps, there is a need to strategically connect pedagogical and curriculum development to eliminate inequities for all students. UDL instructional practices account for not only student variability relating to engagement, purpose, and motivation within the classroom but also in providing educationally diverse learning environments so that all students may benefit and access grade-level standards and academic rigor. General digital tools, from Internet-enabled devices to assistive software, are in support of UDL principles, which allow for self-differentiated learning, and authentic assessments, and should be considered in a complete curriculum (Kurtts et al., 2012). As directed by the school committee, GDRSD must pursue radical new measures to close the academic achievement gaps within subgroups of students, including the economically disadvantaged. These actions will require a strategic shift to increase the rigor of grading practices, further development of data-decision making in support of instructional changes, and define programming for the whole child, including social and emotional learning, and expand special subject programs offerings. Also in consideration are the programmatic changes sought to support all students in a growth mindset, where each child understands that their talents and abilities can be developed through effort, quality teaching, and persistence (Dweck, 2006).

Definition of Terms

Academic Intervention: An academic or behavioral instructional scaffold to support students’ improvement with a specified task (i.e. reading, writing) to meet the needs of all learners (tier 1). In addition, there is a range of tier 2 and 3 academic interventions targeted to specific skills/needs of the student and identified by assessment data (Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education, n.d.).

Economically disadvantaged: Defined as a student’s participation in one or more of the following state-administered programs: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Transitional Assistance for Families with Dependent Children (TAFDC); the Department of Children and Families (DCF) foster care program; and MassHealth (Medicaid) (Redefining low income, n.d.).

Inequality: Unfairness, a lack of equality or justice.

Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS): ESSA (2015) notes this system is “a comprehensive continuum of evidence-based, systemic practices to support a rapid response to students’ needs, with regular observation to facilitate data-based instructional decision making’’ (p. 2093).

Massachusetts Curriculum Framework: Provides all stakeholders with the expectations of what all students understand and are able to perform at the end of each grade level. The standards formalize expectations for all students to have access to similar academic content, regardless of location and abilities (English Language Arts and Literacy, 2017).

Universal design for learning (UDL): A “framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn” (Cast, 2018).

Variability: An understanding that all individuals have a unique learning profile and educators when incorporating universally designed instruction, would embrace these differences and design ways for all students to become expert learners (Stanford Schwab Learning Center, n.d.).

References

- 2019 Official Accountability Report. (2019). School and District Report Cards – Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. DESE. http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/accountability/report/district.aspx?linkid=30&orgcode=06730000&orgtypecode=5&

- About us – GDRSD district. (2020). GDRSD.org. http://gdrsd.org/about-us/

- Allington, R., McGill-Franzen, A., Camilli, G., Williams, L., Graff, J., Zeig, J., Zmach, C., & Nowak, R. (2010). Addressing Summer Reading Setback Among Economically Disadvantaged Elementary Students. Reading Psychology, 31(5), 411–427. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/02702711.2010.505165

- Ander, R., Guryan, J. & Ludwig, J. (2016, March). Improving academic outcomes for disadvantaged students: Scaling up individualized tutorials. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Full-Paper-1.pdf

- Amaral, O. M., Garrison, L., & Klentschy, M. (2002). Helping English learners increase achievement through inquiry-based science instruction. Bilingual Research Journal, 26(2), 213–239.

- Barnum, M. (2019, April 12). Nearly a decade later, did the Common Core work? New research offers clues. Chalkbeat. https://chalkbeat.org/posts/us/2019/04/29/common-core-work-research

- Calkins, L., Hohne, K. B., & Robb, A. K. (2015). Writing pathways: performance assessments and learning progressions, Grades K-8. Heinemann.

- CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Clariana, R. (2009). Ubiquitous wireless laptops in upper elementary mathematics. The Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 28(1), 5–21.

- Department of transitional assistance. (2020). Mass.gov. https://www.mass.gov/economic-assistance-cash-benefits

- Drent, M., & Meelissen, M. (2008). Which factors obstruct or stimulate teacher educators to use ICT innovatively? Computers & Education, 51(1), 187–199. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.001

- Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Elmore, R. (2004). School reform from the inside out: Policy, practice, and performance. Harvard Education Press.

- English Language Arts and Literacy. (2017). Massachusetts curriculum framework for English language arts and literacy: Grades pre-kindergarten to 12. Department of Education. http://www.doe.mass.edu/frameworks/ela/2017-06.pdf

- ESSA (2015). Every student succeeds act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-95 114 Stat. 1177 (2015-2016). U.S. Department of Education. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ95/PLAW-114publ95.pdf

- Freedberg, L. (2019, September 19). Poverty levels in schools key determinant of achievement gaps, not racial or ethnic composition, study finds. EduSource.org. https://edsource.org/2019/poverty-levels-in-schools-key-determinant-of-achievement-gaps-not-racial-or-ethnic-composition-study-finds/617821

- Garcia, E. & Weiss, E. (2017, September 27). Reducing and averting achievement gaps: Key findings from the report ‘Education inequalities at the school starting gate’ and comprehensive strategies to mitigate early skills gaps. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/files/pdf/130888.pdf

- Gershenson, S. (2020). Great expectations: The impact of rigorous grading practices on student achievement. Fordham Institute. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/great-expectations-impact-rigorous-grading-practices-student-achievement

- Gilmore, S., & Ross, D. (2020). Integrating technology: A school-wide framework to enhance learning. Heinemann.

- Guthrie, J.T., Coddington, C.S. & Wigfield, A. (2009). Profiles of reading motivation among African American and Caucasian students. Journal of Literacy Research, 41(3), 317–353.

- Hall, T. E., Cohen, N., Vue, G., & Ganley, P. (2015). Addressing Learning Disabilities With UDL and Technology: Strategic Reader. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(2), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948714544375

- Hattie, J. (2018). Hattie ranking: 252 influences and effect sizes related to student achievement. VisableLearning.org. https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement/

- Huerta, M., Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., & Irby, B. J. (2014). Developing and Validating a Science Notebook Rubric for Fifth-Grade Non-Mainstream Students. International Journal of Science Education, 36(11), 1849–1870. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/09500693.2013.879623

- Howse, R. B., Lange, G., Farran, D. C., & Boyles, C. D. (2003). Motivation and Self-Regulation as Predictors of Achievement in Economically Disadvantaged Young Children. Journal of Experimental Education, 71(2), 151. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/00220970309602061

- Kurtts, S., Dobbins, N., & Takemae, N. (2012). Using assistive technology to meet diverse learner needs. Library Media Connection, 30(4), 22–23. http://search.ebscohost.com.une.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=70426672&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Larkin, M. (2019). How Massachusetts lost count of its poor students. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/edify/2019/08/01/low-income-count

- Lee, O., Deaktor, R. A., Hart, J. E., Cuevas, P., & Enders, C. (2005). An instructional intervention’s impact on the science and literacy achievement of culturally and linguistically diverse elementary students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(8), 857 –887.

- Leithwood, K., Louis, K.S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. The Wallace Foundation.

- Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education. (n.d.). Multi-tiered system of support blueprint. Systems for Student Success Office. http://www.doe.mass.edu/sfss/mtss/blueprint.pdf

- Marion, R. & Gonzales, L.D. (2014). Evolution of the organizational animal. In Leadership in Education: Organizational Theory for the Practitioner. Waveland Press.

- Meyen, E. (2015). Significant Advancements in Technology to Improve Instruction for all Students: Including Those With Disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 36(2), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514554103

- Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

- Meyer, C. B., & Stensaker, I. G. (2006). Developing capacity for change. Journal of Change Management, 6(2), 217-231. https://10.1080/14697010600693731

- Moore, E. J., Smith, F. G., Hollingshead, A., & Wojcik, B. (2018). Voices From the Field: Implementing and Scaling-Up Universal Design for Learning in Teacher Preparation Programs. Journal of Special Education Technology, 33(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643417732293

- Nepo, K. (2017). The Use of Technology to Improve Education. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46(2), 207–221. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9386-6

- Ng, C. (2018). Using student voice to promote reading engagement for economically disadvantaged students. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(4), 700–715. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12249

- Prestridge, S. (2012). The beliefs behind the teacher that influences their ICT practices. Computers & Education, 58(1), 449–458. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.028

- Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

- Rudduck, J. & Fielding, M. (2006). Student voice and the perils of popularity. Educational Review, 58(2), 219–231.

- Redefining low income – A new metric for K-12 education. (n.d.). Department of Education. http://www.doe.mass.edu/infoservices/data/ed.html

- Russell, M., Bebell, D., & Higgins, J. (2004). Laptop learning: A comparison of teaching and learning in upper elementary classrooms equipped with shared carts of laptops and permanent 1:1 laptops. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 30, 313–330. https://doi:10.2190/6E7K-F57M-6UY6-QAJJ

- Sang, G., Valcke, M., van Braak, J., Tondeur, J., & Zhu, C. (2011). Predicting ICT integration into classroom teaching in Chinese primary schools: Exploring the complex interplay of teacher-related variables. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 160–172. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00383.x

- Schacter, J., & Jo, B. (2005). Learning when school is not in session: a reading summer day-camp intervention to improve the achievement of exiting First-Grade students who are economically disadvantaged. Journal of Research in Reading, 28(2), 158–169. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2005.00260.x

- Schmoker, M. (2020). Radical reset: The case for minimalist literacy standard. Educational Leadership, 77(5), 44-50. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb20/vol77/num05/Radical-Reset@-The-Case-for-Minimalist-Literacy-Standards.aspx

- Stanford Schwab Learning Center. (n.d.). Learner variability. Stanford University. https://slc.stanford.edu/learner-variability

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316628645