Abstract: Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools is a pre-kindergarten through twelfth-grade school district with an enrollment of approximately 2,500 students. The five schools are located approximately 40 miles of Boston, Massachusetts, conveniently located near Interstate Route 495. The district features a dynamic leadership team, an outstanding faculty, and a supportive parent community. The towns of Groton and Dunstable are unique in with quaint downtown areas that boast a wonderful history and fine dining experiences as well as rural charm, complete with several working dairy farms in the community.

Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools is meeting or exceeding most accountability measures as reported by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2018 District Report Card, 2018). Even by xceeding state measures, the school committee has tasked the Superintendent as well as the district level administration team, among other initiatives, to create classroom environments for innovation.

One way to create classroom environments for innovation and increase achievement for our middle school students will be to implement a One-to-One initiative with a foundation built on a Massachusetts Frameworks-supported curriculum and a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) instructional model.

Students in elementary grades successfully work in technology-rich learning environments. In third and fourth grade classrooms, students have used Google Chromebooks in a One-to-One environment for deeper engagement within the existing curriculum. With successful connections made at the elementary level, the Department of Technology & Digital Learning is providing middle school students in grades five through eight with a district assigned Chromebook, for use during the school day.

Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools Purpose of Initiative

By way of background, there are ever-increasing expectations that surround online, high stakes, state standardized assessments, namely the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS). District administration alongside teachers has brainstormed some possible ideas to support these expectations for continued student growth and achievement on these tests. Specifically, mathematics and English language arts MCAS scores have recently dropped between fourth and fifth grades. There are other, general, downward trends among many different middle school cohorts transitioning between various grades. An area that has been called out by the school committee is student growth in various accountability subgroups. Examples of subgroups are economically disadvantaged students or students with disabilities as defined by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

To implement an innovative approach, such as this One-to-One initiative on a district foundational principle of Universal Design for Learning, the district must first establish a financially sustainable model and engage with stakeholders. Topper and Lancaster (2013) shared the importance of planning for the implementation of a One-to-One initiative, calling this aspect a critical component for success. For the upcoming 2020 fiscal year, ending June 30, 2020, the Department of Technology & Digital Learning received the necessary financial support from the school committee and district administration to implement a One-to-One initiative at the middle school. Teachers will receive professional development, aligned to meaningful technology integration and UDL, as well as support for best practices and constructive feedback through the teacher evaluation system.

Topper and Lancaster (2013) indicate that in addition to financial planning and a strong commitment to integrating technology, a vision on the role technology plays is also a critical component for success. A clear vision and communication strategy is key:

Absent this commitment, the ultimate success of a One-to-One initiative is difficult to evaluate and may result in contrary or confusing messages. This is not just an issue of management, but communication, developing and sharing a vision for the role of technology, getting support from the community, and establishing clear outcomes of success. In districts that participated in this study, a clear vision of the role of technology in supporting learning and a sustained commitment from administrators at all levels was apparent. (Topper & Lancaster, 2013, p. 352)

Mindful of pitfalls outlined by Topper and Lancaster (2013), the district has been visible with stakeholders and shared considerable communication with middle school faculty and the community-at-large for the innovative approach of providing each student with a Chromebook. This two-way, home-school connection is important and will continue throughout the initiative. There is also a community-created vision and mission statement, that was devised over a two-day strategic planning session with all stakeholders represented.

Research has come to various conclusions surrounding the benefits of general technology in the classroom, regularly sharing positive correlations. Wanting to align the initiative and funding to research-based principles and best practices, we have looked to provide substantiated evidence to stakeholders on the benefits. For example, Clariana (2009) conducted a quantitative study that compared middle school students’ math test scores in One-to-One environments. Clariana (2009) found that middle school students with One-to-One access “performed better than those in schools with 1:5 programs [one device for five students]” (p. 7). Clariana (2009) hypothesized this increase in mathematical achievement was likely due to innovative instructional approaches that teachers were able to implement with access to a One-to-One program.

Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools Stakeholders

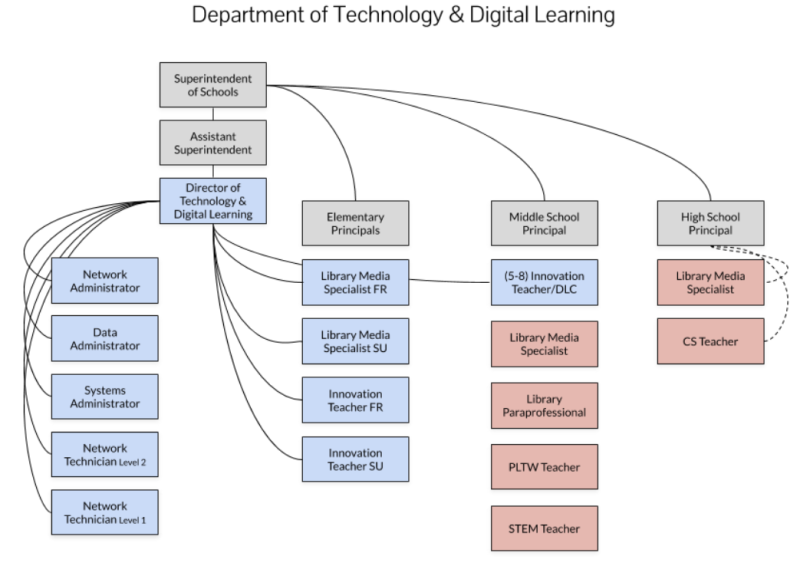

Across Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools, there are many direct stakeholders such as faculty, support staff, students and parents. There are also many indirect stakeholders with various degrees of involvement, which include the school committee, taxpayers within the community and elementary and high school level administration. The Department of Technology & Digital Learning will take on a majority of support for the initiative, facilitation of professional development and leadership to ensure the success of this One-to-One program.

To properly support the One-to-One rollout and with many other demands, various district initiatives on the docket for the upcoming school year (i.e. blended learning, social-emotional learning, integrating new science curricula, etc.), the Department of Technology & Digital Learning will increase the team by an additional Network Technician. This position will allow for a more robust system necessary to support not only the One-to-One Chromebook initiative at our middle school, but also broader support needed for infrastructure, hardware, and software in our 21st-century learning environments.

From experiences in past technology-related rollouts, although the student is the primary beneficiary of the collective effort, almost just as important of a stakeholder, tied to a successful One-to-One implementation, are the faculty and support staff. Topper and Lancaster (2013) found that faculty readiness and preparedness are important during the beginning phases of technology innovation, specifically in their research of students in a One-to-One laptop program and the faculty structure and communication skills needed to be successful. Topper and Lancaster (2013) suggest identifying those faculty not ready to be part of the innovative process, needing professional development, and to allow time for faculty to discuss concerns before the rollout.

Maninger and Holden (2009) shared concerns about difficulties teachers had in creating a learning environment, “where learning drives the use of technology, instead of the other way around” (p. 7). Identifying these points of potential pressure points before the initiative is allowing for a more meaningful, teacher-centered approach to the role out. Through direct communication with teachers along with monthly grade-level and administrative team meetings, we are working on being proactive before and during the initiative.

Organizational chart

Mission statement

In cooperation with the parents and the community, is committed to providing the best possible education for each student. It is our responsibility to promote in each child a spirit of inquiry and to instill a self-sustaining desire for continuous growth and service to self, family, and community.

Change Initiative Intentions

To meet the needs of the middle school One-to-One Chromebook initiative, we must ensure students are prepared to thrive in a world that demands collaboration, innovative thinking, and adaptability. Chromebooks are secure (Fang, Hanus, & Zheng, 2019) and support students in the latest collaborative and productivity tools. In addition to security, Chromebooks are becoming an industry-standard device and are affordable, durable, and makeup over half of the devices shipped to the K-12 education market (Mathewson, 2018). These devices allow for deeper engagement within all areas of the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks. We must also ensure that students are developing essential, technology-enriched skills across all content areas, specifically in the areas of mathematics and English language arts, to increase student achievement in MCAS assessments. In these two content areas, in particular, there will be quantitative results in the form of MCAS scoring data, which may be needed to identify successes in the One-to-One program.

As noted, before beginning their academic career at the middle school, students in second, third, and fourth grades have been working in a similar One-to-One environment with Chromebooks. With success for this approach at the elementary level, all students in grades five through eight will have an assigned Chromebook during the school day.

Currently, middle school students use shared Chromebooks available in certain classes and will return it at the end of class. For the upcoming year, each morning, students will pick up their assigned Chromebook, stored on a charging cart, in their homeroom. Students will be responsible for their device throughout the day, carrying it while transitioning between classes, and will return the Chromebook to their homeroom charging cart at the end of the day. Students will respect and care for their Chromebook much as they would with other school property, which is aligned to the building’s “Core Values” found in the middle school handbook.

With the structure in place in terms of equipment, infrastructure, and expectations, as well as an increase in technical support staff, the district must recognize that change takes time and works best in collaborative and immersive environments. Innovative change is fraught with uncertainty and obstacles not only for students but for our faculty. With this in mind, the district has continued to support integrating technology across the curriculum by incorporating concepts of UDL. The creation of standards-based lessons and assessments connected to UDL is tied to the district’s best teaching practices.

Alignment between UDL and the integration of technology exists among a majority of faculty through yearly professional development opportunities and college course offerings within the district. The comfort-level continues to increase each year. For example, one of the core UDL guidelines is providing multiple means of representation or how students receive the transfer of learning. Cast (2008) states the transfer of learning “occurs when multiple representations are used because they allow students to make connections within, as well as between, concepts.” The use of a Chromebook in a One-to-One setting would deepen UDL integration by allowing students to listen to audiobooks, adjust the font size of a text, read subtitles on a video or adjust the text Lexile using available district software. From a teaching point of view, collaborating with students to provide text and/or audio feedback inside a Google Doc, offer resources such as videos for deeper engagement with content and provide students with a choice on how they best can represent their learning through various web tools, are all ways to deepen UDL integration with technology.

Marion and Gonzales (2014) proposed that organizations should make necessary changes with inconsistent performances, or in one of Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools’ examples, declining MCAS assessment scores. Marion and Gonzales (2014) offer a powerful statement on the change that when combined with supporting evidence, “the costs associated with change are less expensive than the costs associated with not changing” (p. 361). One of the most important aspects of our district vision and the changes that come from this One-to-One initiative would be to embrace environments for innovation. Moving toward a One-to-One environment at the middle school is one step closer to realizing this vision.

Leading change in a measured, considerate, and deliberative manner is the type of transformative leadership that will be required for this initiative, differing from the more traditional, top-down leadership style. Reflection and transparency have been built into the One-to-One initiative that will support change and allow for district leadership, through the Director, to correct difficulties and conflicts along the way (Marion & Gonzales, 2014).

Change Initiative Team

Many teams within Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools will become involved in the process and application of the One-to-One initiative. However, for this exercise, the members of the Department of Technology & Digital Learning, specifically the Network Administrator, Systems Administrator, and building-based Network Technicians are working on this initiative alongside the Director. The team members make up a support “core” and would be directly involved with preparing the Chromebooks by adding them to inventory, updating operating systems, applying network settings and adding each Chromebook into the proper management console. As repairs and replacement Chromebooks are needed, the team would be on the frontline for this integral support as well. Important to note, the team will be called on to support deeper levels of integration and technology tools during this initiative outside of typical hardware support. Team members will be called upon to support teachers and staff ineffective uses of Chromebooks, where needed.

Change Initiative Benefits

Although teachers and support staff might be the most important stakeholders in the successful start to the One-to-One initiative, middle school students are the primary beneficiaries of the collective efforts. The teacher and student are intrinsically tied together as what could be viewed for this exercise, as a common stakeholder.

Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, and Chang (2016) conducted a meta-analysis examining the effect of One-to-One laptop programs on teaching or learning and found significantly positive average effect sizes in English, writing, mathematics, and science achievement data. Reported findings by Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, and Chang (2016) and their analysis included a positive increase in the following: frequency and breadth of student technology use, student-centered learning, quantity and genres of writing, and improvements of teacher-student and home-school relationships. Several studies analyzed by Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, and Chang (2016) also reported a significant increase in student engagement, motivation, and persistence with access to a One-to-One program.

Russell, Bebell, & Higgins (2004) used student surveys, teacher interviews, and classroom observations to compare teaching and learning activities between One-to-One laptop classrooms and shared laptop classrooms and noted positive effects. Also, a primary benefit noted in this research was the individualized instruction and the ability for teachers to meet the individual learning needs of their students, was greater when classrooms were equipped with One-to-One laptops. This last factor is greatly in support of the necessary scaffolds that proper UDL implementation requires.

Another objective of this initiative is to increase student achievement to meet the needs of diverse students within the disabilities subgroup. Another essential part of the implementation of UDL would be in support of assistive technology made available to not only students with disabilities on an individualized education plan (IEP) but assistive technology tools that are available for all students. Teachers who understand the principles of UDL in lesson planning consider diverse students’ needs to be the result of normal variance within a heterogeneous population rather than isolated instances of difference or disability (Kurtts, Dobbins, & Takemae, 2012).

Just one of the many subjects the middle school faculty and students will explore, ties back to the Massachusetts Curriculum Framework in English Language Arts and Literacy, specifically the writing standards in grades five through eight. For example, in the Grade 5 Writing Standards, under Production and Distribution of Writing, it states, “Use technology, including current web-based communication platforms, to produce and publish writing as well as to interact and collaborate with others; demonstrate sufficient command of keyboarding skills to type a minimum of two pages in a single sitting” (English Language Arts and Literacy: Massachusetts Curriculum Framework, p. 69).

Exploring the writing process further, Russell, Bebell, & Higgins (2004) shared through classroom observations and teacher interviews, that students in a One-to-One classroom environment viewed their laptop as a primary writing tool, spent more time writing and an increase in the frequency of times spent writing was noted, as compared to students in a shared laptop model. “Students in the 1:1 classes were nearly six times more likely to be observed composing text on a laptop…conversely, students in the shared laptop classroom were eight times more likely to be observed composing text using paper and pencil than with a laptop” (Russell, Bebell, & Higgins, 2004, p. 330). The writing process benefits not only the teacher, many who are actively seeking the tools to take next step(s) in UDL implementation but also supports our students through deeper connections with existing Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks in English language arts.

As it relates to a more general narrative of the initiative and the necessary access to innovative tools, like a Chromebook, Russell, Bebell, & Higgins (2004) noted that the research did provide evidence that in a One-to-One environment, student technology use increased significantly for a variety of academic purposes.

Moving on from the teacher/student stakeholder, we connect to the school committee and local community members, who are looking to the district administration to develop this One-to-One initiative to support our district vision of creating environments of innovation and more granularly, an increase MCAS assessment scores. There is a component of these stakeholders looking for a return on investment (ROI) and how best to provide meaning and actionable goals in this initiative. Although difficult to provide ROI in a traditional sense and may not capture the benefits of the investment in this initiative, we may be able to apply qualitative results through observation and connect back to the financial outlay of funds to maintain the One-to-One program to provide the level of detail these stakeholders may seek.

Building administration, faculty, support staff and the Department of Technology & Innovation must capture this data and be able to report back successes and failures on a timely basis to the school committee and local community, at-large. Although not as important, there will be quantitative results measured by the reduction of costs on physical textbooks as the Chromebook is relied on for a mathematics, science and social studies curriculum. The savings in textbooks can be shown alongside the costs of the lease program for the One-to-One initiative. There will also be software included on the Chromebooks, which will allow analytics on the daily usage of district digital resources. In both cases, the data can be collected and measured to online standardized assessment data and the financial costs of the One-to-One program.

Marion and Gonzalez (2014) shared the meaning of inertia as it relates to both the leader and the organization. They shared why managers may hold off on change because inertia may mask the problems at hand, especially in a more developed organization, such as the case at Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools.

Inertia enables organizational actors to benefit from experience and learning, and this enhances effectiveness and positive selection…Selection favors effectiveness and effectiveness comes from inertia, but inertia can mask and resist needed change. Here is where good leadership may play a role. Good leaders know when it is time to change and when it is not (Matrion & Gonzalez, 2014, p. 361).

With this quote in mind, one of the remaining stakeholders in this change initiative is the Director of Technology & Digital Learning. There is an opportunity in this initiative, if taken seriously and communicated well, will greatly benefit the Director, as it relates to becoming a transformative leader and fighting back the tide of inertia within the district. Wilson (1998, as cited in Bass & Bass, 2008) shared, “leaders should be uncommon (yet congenial, vulnerable, and accessible); capable as almost to promote awe” (p. 55). This initiative is a large undertaking for the Director and the underlying team, with large scale changes across the entire Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools spectrum. This initiative under the leadership of the Director may promote and capture awe for the district and all other stakeholders and the Director will need to employ transformative leadership principles for innovative and transformational changes to occur.

Conclusion

Supporting and exploring technology-rich learning environments where faculty and students are intrinsically tied together to increase student achievement has materialized over the past six years. Tasked by the school committee to create innovative classroom environments and to meet the needs of our diverse learners, the implementation of an official One-to-One initiative, built on a UDL instructional model and the Massachusetts Frameworks, will benefit our middle school students. Profound academic gains are expected and will transpire with financial support for the initiative, professional development opportunities for faculty and a strong commitment to integrating technology and UDL principles as a core tenet and best teaching practice at Groton-Dunstable Regional Schools.

References

- Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2008). Models and theories of leadership. In Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Application (4th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

- CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Clariana, R. (2009). Ubiquitous wireless laptops in upper elementary mathematics. The Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 28(1), 5–21.

- Donovan, L., & Green, T. (2010). One-to-one computing in teacher education. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 26(4), 140-148. https://doi:10.1080/10402454.2010.1078464

- English Language Arts and Literacy. (2017). Massachusetts curriculum framework for English language arts and literacy: Grades pre-kindergarten to 12. Retrieved from http://www.doe.mass.edu/frameworks/ela/2017-06.pdf

- Fang, K., Hanus, D., & Zheng, 2019. Security of Google Chromebook, 1-3. Retrieved from http://dhanus.mit.edu/docs/ChromeOSSecurity.pdf

- Harper, B., & Milman, N. B. (2016). One-to-one technology in K–12 classrooms: A review of the literature from 2004 through 2014. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(2), 129–142. https://doi-org.une.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1146564

- Kurtts, S., Dobbins, N., & Takemae, N. (2012). Using assistive technology to meet diverse learner needs. Library Media Connection, 30(4), 22–23. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.une.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=70426672&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Maninger, R. M., & Holden, M. E. (2009). Put the textbooks away: Preparation and support for a middle school one-to-one laptop initiative. American Secondary Education, 38(1), 5-33. Retrieved from https://une.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.une.idm.oclc.org/docview/61817267?accountid=12756

- Marion, R. & Gonzales, L.D. (2014). Evolution of the organizational animal. In Leadership in Education: Organizational Theory for the Practitioner (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Mathewson, T. G. (2018, March 28). Laptops, Chromebooks or tablets? Deciding what’s best for the nation’s schools. The Hechinger Report Retrieved from https://hechingerreport.org/laptops-chromebooks-or-tablets-deciding-whats-best-for-the-nations-schools

- Russell, M., Bebell, D., & Higgins, J. (2004). Laptop learning: A comparison of teaching and learning in upper elementary classrooms equipped with shared carts of laptops and permanent 1:1 laptops. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 30, 313–330. https://doi:10.2190/6E7K-F57M-6UY6-QAJJ

- Topper, A., & Lancaster, S. (2013). Common challenges and experiences of school districts that are implementing one-to-one computing initiatives. Computers in the Schools, 30(4), 346-358. https://doi:10.1080/07380569.2013.844640

- 2018 District Report Card. (2018). School and District Report Cards – Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Retrieved from http://reportcards.doe.mass.edu/2018/DistrictReportcard/06730000?Length=8

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316628645