With an existing, underutilized digital portfolio system and a universally designed instructional model, students have the opportunity to improve scoring on the MCAS, specifically English language arts writing standards, within the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks. GDRSD must look to greater utilization of an educational tool such as a digital portfolio to improve state-standardized assessment scores.

Background

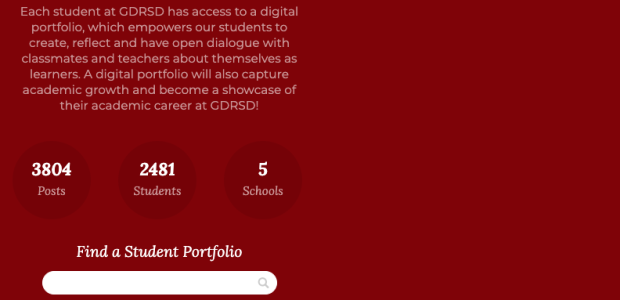

The Groton-Dunstable Regional School District (GDRSD) is a pre-kindergarten through the twelfth-grade regional district with a current enrollment of approximately 2,500 students. GDRSD’s five schools, across six buildings and two towns, are situated 45-miles, northwest of Boston, Massachusetts. The district features a strong leadership team, an outstanding faculty, and a supportive and engaged parent community. GDRSD is considered a high-achieving district and has opened its doors to educators from around the world looking to observe successful teaching practices.

As reported by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), GDRSD is meeting or exceeding nearly all accountability measures across annual assessments on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). On overall progress toward student growth targets, GDRSD has a cumulative criterion-referenced target percentage of 84% (2019 Official Accountability Report, 2019). This target percentage signifies how GDRSD is doing compared to other districts across the state. In GDRSD’s case, the district is meeting and/or exceeding their student growth targets better than 84% of districts within Massachusetts. However, upon further inspection of subgroups within the larger DESE indicators, 49% of students belonging to at least one of the following subgroups: students with disabilities, English language learners, or low-income students, are not meeting their targeted growth goals in English language arts (Glossary of accountability reporting terms, 2019). As a motivator and tool for engagement, incorporating digital portfolios can allow for deeper connections within the curriculum and an ability to capture a stronger body of evidence toward mastery of the anchor standards for writing within the Massachusetts Curriculum Framework. Further, within the pre-K–5 College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Writing, there is a heavy emphasis on building truly robust writing skills noting “students must devote significant time and effort to writing, producing numerous pieces over short and extended time frames throughout the year” (English Language Arts and Literacy, 2017, p. 22).

The GDRSD school committee has tasked district leadership with a goal of fostering innovative classroom environments. With this directive set forth, students are learning in instructional sound, technology-rich learning environments, with access to Google Chromebooks, Apple iPads, and Windows-based computer-labs (Callahan, 2016). Students in second through eighth grade, are provided a Google Chromebook, as a part of a formal 1:1 initiative, in support of access to technology for students. There are positive conclusions surrounding the benefits of technology in the classroom, regularly sharing positive effects in English language arts achievement data (Clariana, 2009; Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, and Chang, 2016). With the technical infrastructure in place across GDRSD needed for successful digital learning, such as fiber optic cables and high-speed wireless internet, educational efforts can be focused on the software impacting students, such as digital portfolios, and best practices that can increase student achievement and support the needs of diverse students within subgroups.

Analysis

Digital portfolios are highly motivating for students, allowing them to share with an audience outside the walls of the classroom (Anderson & Mims, 2014). Equally motivating for students is the foundational idea that effective instruction requires frequent assessments, especially within the wiring process, to identify student’s strengths and weaknesses and to adjust future instruction. As students devote considerable time and becoming “adept at gathering information, evaluating sources, and citing material accurately” (English Language Arts and Literacy, 2017, p. 132), students must also be able to use technology strategically when creating, refining, and collaborating on writing” (p. 132).

Further, Berger (2003) suggests that a teacher shouldn’t be the sole judge of a student’s work and no matter the audience size, albeit peers or a national audience, teachers should help their students share quality work. In the process of growing academically, Kleon (2014) takes it a step further, sharing students should commit to learning in front of others no matter the quality. In an interview with educational researcher Dr. David Niguidula, Zmuda (2012) captured Niguidula’s ideas on how digital portfolios allow students to show how they arrive at proficiency and demonstrate current academic achievements. In addition to tracking progress towards mastery of writing standards, digital portfolios allow for what Berger, Rugen, & Woodfin (2014) share as ‘portfolio events’, which are opportunities during the school year for students to control their learning and to share and reflect in student-led conferences.

With equitable access to technology, through 1:1 computing environments at GDRSD, digital portfolios and the Massachusetts Curriculum Framework in English Language Arts and Literacy can be combined into a powerful combination in documenting and representing mastery of writing standards. For example, within the grade five Writing Standards, under Production and Distribution of Writing, it states that students, “Use technology, including current web-based communication platforms, to produce and publish writing as well as to interact and collaborate with others” (English Language Arts and Literacy: Massachusetts Curriculum Framework, p. 69). A digital portfolio is a strong way to document mastery of this writing standard.

To explore the writing process further, specifically with students in 1:1 computing environments, Russell, Bebell, & Higgins (2004) share in their research, through classroom observations and teacher interviews, that students view their laptop as a primary writing tool and observed an increase in the frequency of both time spent and number of opportunities to write, using a 1:1 computing device. “Students in the 1:1 classes were nearly six times more likely to be observed composing text on a laptop” (Russell, Bebell, & Higgins, 2004, p. 330) when compared to students using paper and pencil. A digital portfolio supports writing and technology-related standards through meaningful and deeper connections with existing Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks in English language arts.

Proposed Solutions

The Department of Technology & Digital Learning (Department) at GDRSD has designed a custom digital portfolio system with an open-source content management system called WordPress Multi-Site. GDRSD believes WordPress Multi-Site “empowers students to create, reflect and have an open dialogue with classmates and teachers…provid[ing] a single, organized space [that is] device agnostic and great use of our existing technology” (Callahan, 2015). A great deal of attention and energy has taken place in the development of this digital portfolio system to assure students are able to seamlessly access the portfolio using their Google Apps for Education (G Suite) accounts. With digital portfolios not only capturing what students create but also the how and why at each grade level, it is important that the district provides a single, secure portfolio for every student over the entirety of their academic career (Callahan, 2016).

As a way to support students in meeting their targeted growth goals, the district vision of implementing universal design for learning principles (UDL) within the curriculum is important to note. UDL can be best defined as the “framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all” (Cast, 2018). Digital portfolios are in support of these UDL principles and is a tool that allows for both self-differentiated learning and assessments, and should be considered in support of a complete curriculum and in support of the diverse needs of all students (Kurtts, Dobbins, & Takemae, 2012).

Advancements between the Department and the Office of Curriculum and Instruction are necessary to connect digital portfolios to the existing curriculum. A digital portfolio should not be seen as a piece of software, disconnected from the curriculum and without standing within our UDL instructional model and the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks. Instead, a digital portfolio is integral to the success of a district with a vision in support of innovative classrooms, and engaging students “ready to become positive contributors to local and global communities” (About us – GDRSD district, 2019). With research in support of, and frequent attempts by the Department lauding the benefits of digital portfolios, further edicts for usage should come from the Office of Curriculum and Instruction.

Conclusion

In order for digital portfolios to be deemed worthy of attention, teachers, students, and administrators must see the value in the process of capturing learning, specifically the writing process. With the Department providing a strong, capable software to maintain portfolios, along with a connection to existing cloud-based accounts, the technology setup is foundational and ready for the next step(s). Potentially seen as a more macro-level view, research supports the practice of learning in front of others and sharing to an audience outside the school walls. As we focus more granularly within GDRSD, with UDL, Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks, and innovation as a driver for quality instruction, a digital portfolio allows every student to showcase their best efforts and mastery of writing standards within the curriculum. The Department will need a great deal of support from district level departments in properly providing teachers with professional development and to make connections as to why digital portfolios are necessary.

In addition to identifying accountability measures in English language arts using annual MCAS results, the district should focus on formative assessments employing grade-level writing assessments. Throughout the year, effective instruction must provide students with frequent opportunities to monitor progress towards mastery of writing standards. Assessments can provide not only a way for students to reflect on their writing and for teachers to plan future instruction based on strengths and weaknesses, but writing samples can also be captured on a digital portfolio. After completion of a formative writing assessment employing a rubric for fluency and content, writing samples can be shared to a digital portfolio post, sharing beyond the classroom walls. After publication to the digital portfolio, peers and staff can provide feedback in support of modeling digital citizenship as well as allowing for further self-reflection of the writing process. Digital portfolios are an educationally sound tool for improving writing and engaging students within the existing curriculum.

References

- 2019 Official Accountability Report. (2019). School and District Report Cards – Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Retrieved from http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/accountability/report/district.aspx?linkid=30&orgcode=06730000&orgtypecode=5&

- About us – GDRSD district. (2019). Retrieved from http://gdrsd.org/about-us/

- Anderson, R., Mims, C. (2014). Handbook of research on digital tools for writing instruction in K-12 settings (1st ed.) Information Science Reference: US.

- Berger, R. (2003). An ethic of excellence: Building a culture of craftsmanship with students (1st ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip042/2003007290.html

- Berger, R., Rugen, L., & Woodfin, L. (2014). Leaders of their own learning: Transforming schools through student-engaged assessment (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Callahan, L. (2015). About digital portfolios – GDRSD portfolios. Retrieved from http://portfolio.gdrsd.org/about/

- Callahan, L. (2016). GDRSD strategic technology plan FY17-21. Groton-Dunstable Regional School District, 30-31. Retrieved from http://gdrsd.org/departments/technology/

- CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Clariana, R. (2009). Ubiquitous wireless laptops in upper elementary mathematics. The Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 28(1), 5–21.

- English Language Arts and Literacy. (2017). Massachusetts curriculum framework for English language arts and literacy: Grades pre-kindergarten to 12. Retrieved from http://www.doe.mass.edu/frameworks/ela/2017-06.pdf

- Glossary of accountability reporting terms. (2019). Retrieved from http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/accountability/report/aboutdata.aspx

- Kleon, A. (2014). Show your work!: 10 ways to share your creativity and get discovered (1st ed.). New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company.

- Kurtts, S., Dobbins, N., & Takemae, N. (2012). Using assistive technology to meet diverse learner needs. Library Media Connection, 30(4), 22–23. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.une.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=70426672&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Russell, M., Bebell, D., & Higgins, J. (2004). Laptop learning: A comparison of teaching and learning in upper elementary classrooms equipped with shared carts of laptops and permanent 1:1 laptops. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 30, 313–330. https://doi:10.2190/6E7K-F57M-6UY6-QAJJ

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316628645

- Zmuda, A. (2012). How digital portfolios document and motivate learning. Retrieved from https://www.learningpersonalized.com/david-niguidula-on-digital-portfolios/